In the projects I’ve worked on, about half of them skipped any sort of design phase. This typically lead to unmanageable code a few months into the project with no discernible way to backtrack or quickly change architecture. While each project could benefit from their own postmortem on their design phase (or lack thereof), I’m going to focus on the commonalities between projects that had some form of design phase and projects that did not. Feel free to use this as a guide for your future projects.

The Good

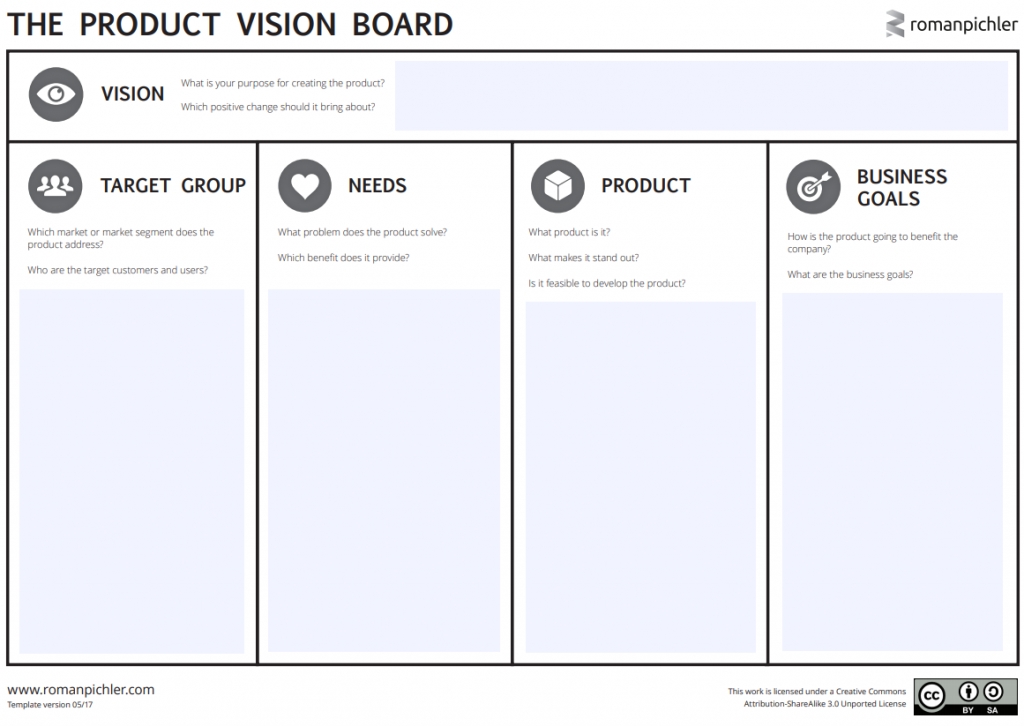

A design phase can be beneficial for any project. It provides a moment to think about the solution and how the architecture for it can be developed modularly with reusability and maintainability in mind. Do not underestimate this phase! This is where deep thought occurs in how the system should be developed and how the system is intended to be used. APIs are designed during this phase which will determine how the system interacts with itself and other services. A good design at this phase results in cheaper development and cheaper maintenance.

While design is important, there is a diminishing return on investment in design. The more time spent on designing a system without implementation, the less valuable it becomes. Development teams should be cognizant of their time spent designing and, after a high level design, begin designing the first thing to implement. Iterative designing alongside developing results in a flexible work plan and a flexible architecture or API design. The idea with a lightweight and iterative design process is that future design improvements build on top of or extend the existing design. Any future work that requires a re-write highlights the lack of understanding of the original requirements or a design that is inflexible. A good barometer of when a design has “enough” value is when the software engineers understand the system they are about to begin developing.

In addition to understanding a system before implementing it, design provides a blueprint for enabling test-driven development. Designed APIs may have tests written against the expected behavior of the implemented logic before any logic is actually implemented. This type of testing leads to clean and clear requirements alongside understanding of how the system should operate after implementation.

The Bad

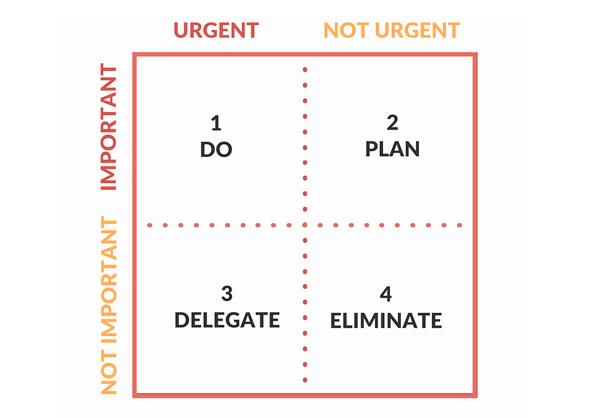

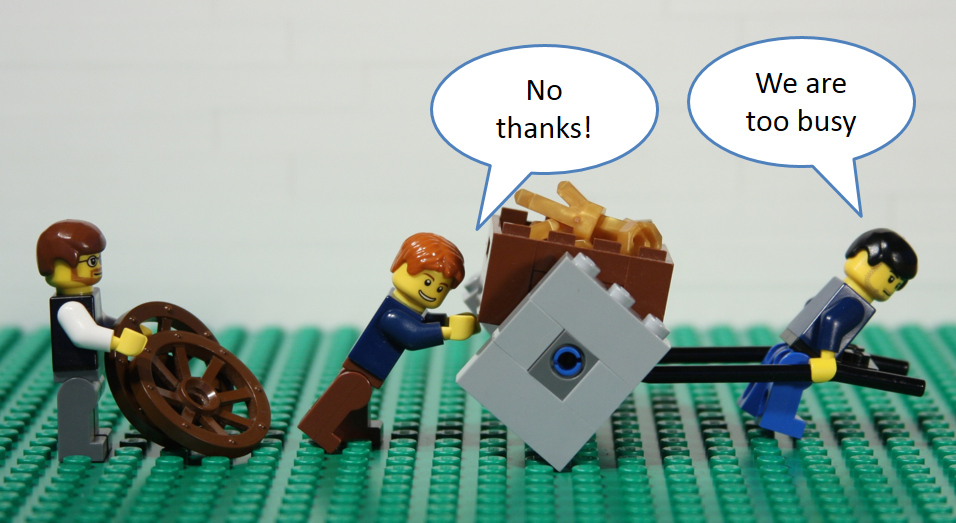

So, why don’t teams design? The perceived cost to design in terms of time (and we all know time equals money) may not generally seem to be all that valuable to project management. Why spend time thinking about the project when you can just jump right in and start making it? This perceived cost saving measure of cutting or severely reducing design time isn’t necessarily tangible to project managers. Project managers typically care about actions that move the needle forward. Design does not move the needle forward — it moves the needle faster.

Because design is cut from the process, a lot of time is spent re-implementing, re-working, or refactoring code. Developers often code themselves into a proverbial corner and find the system that they have build is not easily adaptable to a new feature that needs implementation. This new feature requires refactoring the existing code. This refactoring doesn’t have an opportunity for a design phase. And the implemented feature is later refactored again when some other new feature needs implementation. This is a vicious cycle that often becomes the status quo and the team’s productivity quickly plummets (not to mention morale).

Furthermore, with all of this rewriting and refactoring, the system and the team’s understanding of this system, are not guaranteed. The system is a hodgepodge of various hacks and quick fixes that it is effectively held together by “magic.” I’ve been on a project where this “magic” ended up preventing new features and we ended up tracing the logical flows. This lead us to discover that there was a nasty bug in logical flow that wasn’t expected and would not have otherwise been discovered. What was worse was that we couldn’t fix this bug without declaring technical bankruptcy and reworking the architecture to achieve the intended (and expected) results.

The Ugly

Let’s talk about the ugly truth of any code base, regardless of good, bad, or no design: technical debt. Ward Cunningham coined this term and it is an analogy to treating deficiencies in a software product as a loan that accrues interest. The longer a deficiency persists in a system, the more technical debt it accrues. A project can accumulate so much technical debt that forward progress is no longer possible and the project must declare technical bankruptcy. This bankruptcy results in either a failed project, or a rewrite of part or the whole system. Martin Fowler has a lovely article that describes this concept in wonderful detail.

Following this same analogy, consider design a down-payment on a project. Sure, you can certainly start working on a project without a design, but you will quickly start accruing technical debt and that debt will accrue faster. Do yourself a favor and work in a design whenever you need to refactor something and before you start working on the code! Coding without a plan is what typically gets a software team stuck in technical bankruptcy. Don’t repeat what got you there when you dig yourself out!

Wrap up

Knowing all of this, it’s easy to see the value in design. Building a system without a plan has large hidden costs. Refactoring without a plan compounds these costs. When you don’t have a design phase at all you are essentially earmarking money to burn down the road with more time re-developing parts of your system until you can’t move that needle at all.